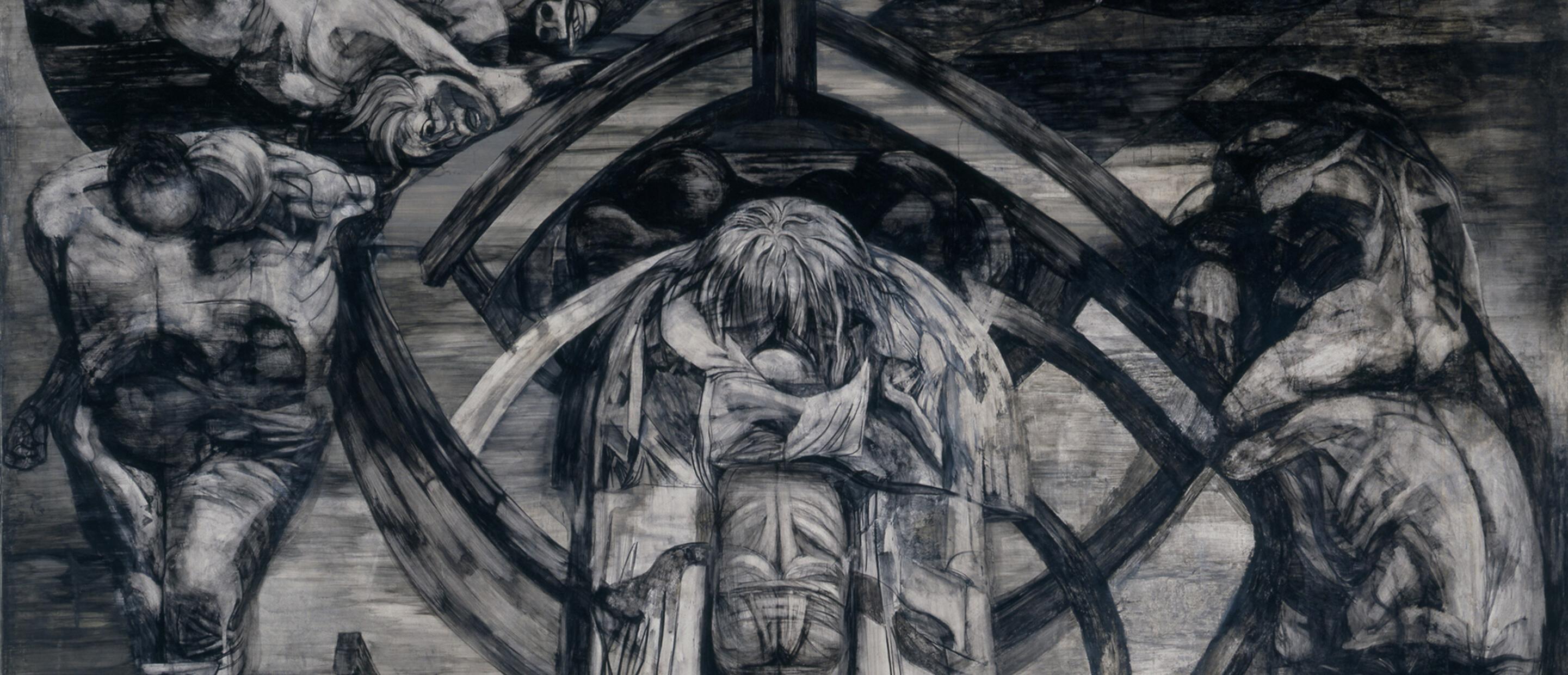

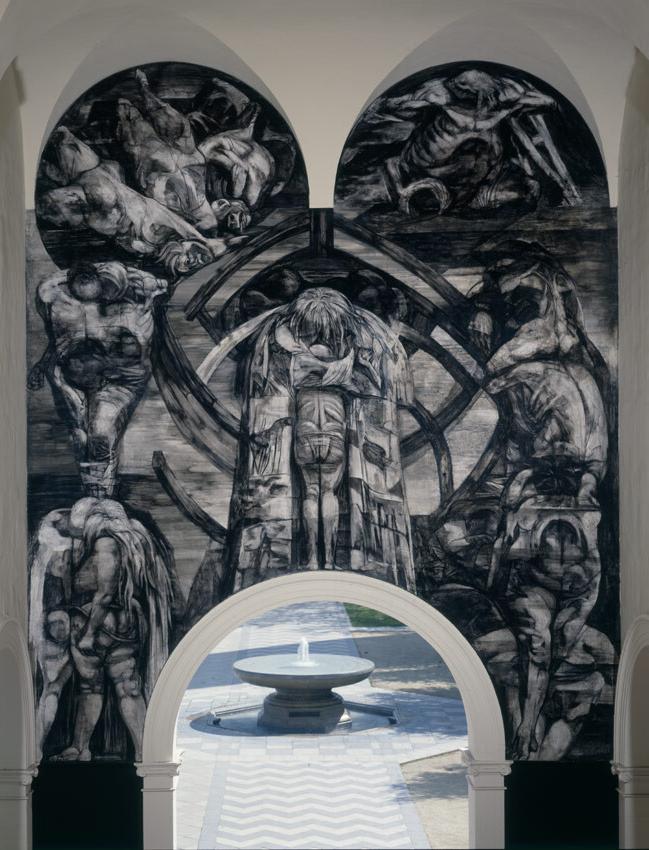

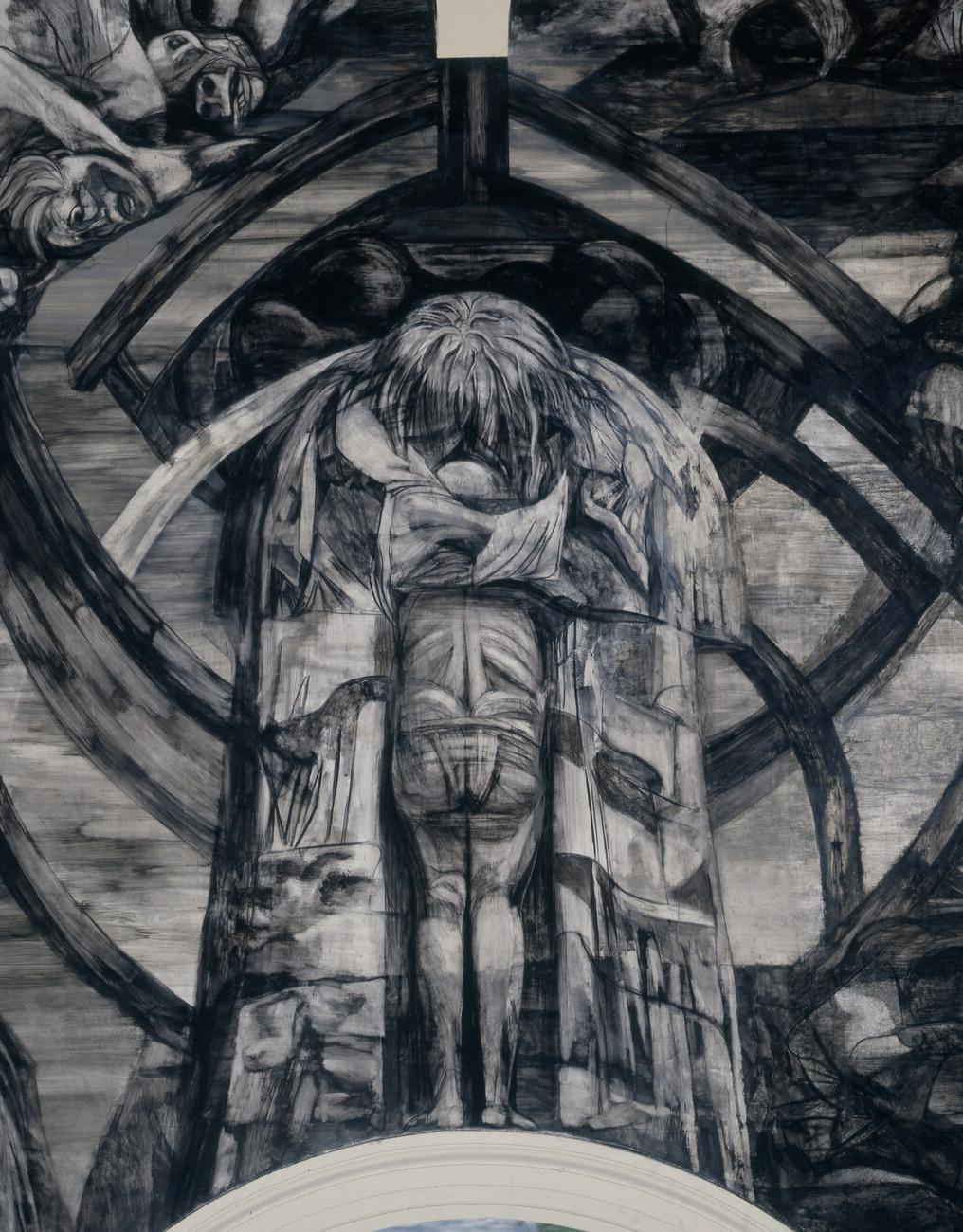

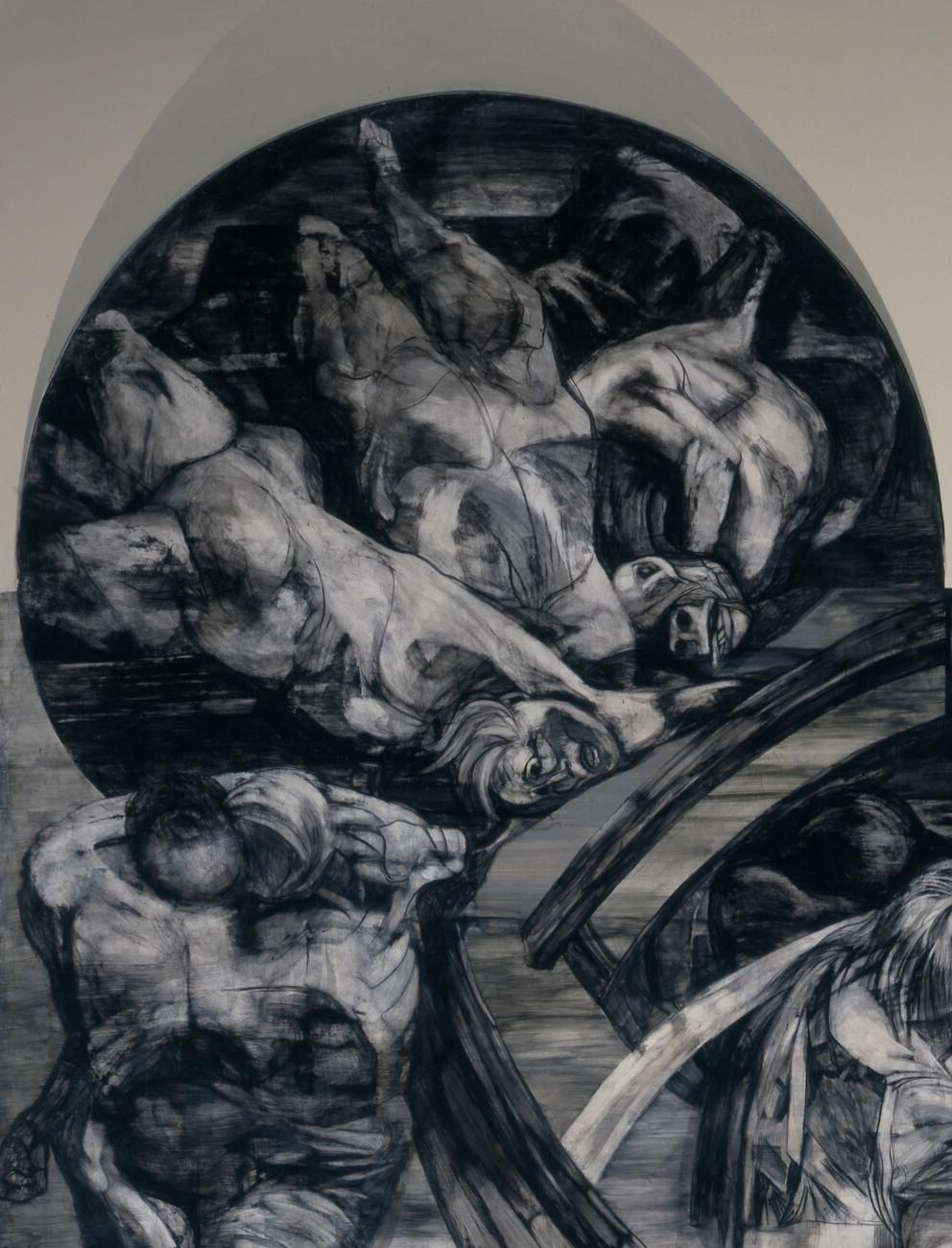

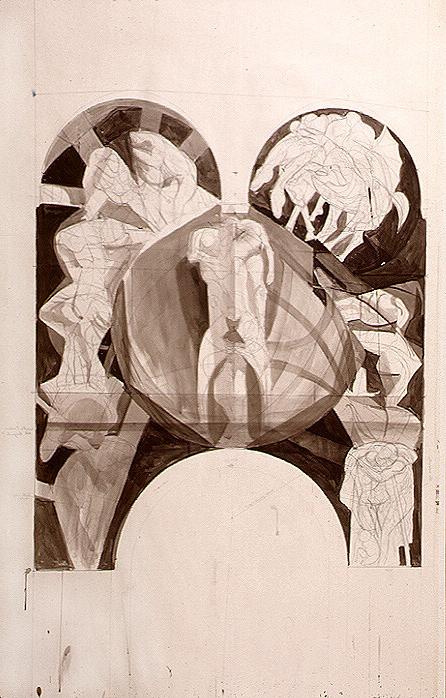

Rico Lebrun (1900-1964) painted the Genesis mural on the interior wall of the south entrance of Frary Hall in 1960. Along with Jose Clemente Orozco's Prometheus mural, it is one of the most important artistic treasures of Pomona College. The monumental figure of Noah sheltering a child (shown in the image here) serves as the mural's visual and symbolic center, while surrounding Noah are representations of the Deluge, Job, Sodom and Gomorrah, Cain and Abel, and Adam and Eve.

Although Lebrun did not offer a specific reason for selecting the theme of Genesis, the subject was consistent with the religious content of his previous work. Lebrun's first concept for the wall was to portray, "the evolution of form," and he spoke at the time of "half-borrowing and half-inventing organic fragments, skulls, sections of backbones, sections of ribcages, roots of plants, geological formations...to weld some kind of design which would put across the becoming of form." The story of Creation lent itself to this goal while also accommodating the artist's personal philosophy that understood reality as a complex interweaving of ideas, an inextricable blending of opposites, where good and evil existed side by side. With its epic events and universal themes, the story of Genesis provided the narrative framework for what was to be a highly personal aesthetic and political At the same time, Lebrun was quick to acknowledge his sources, whether in the work of other artists, in nature, or in contemporary events. The compositional structure of the mural, its individual pictorial units integrated into a monumental whole, mirrors a blending of artistic influences--Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, Italian Baroque painting, Picasso's Guernica, among others--with the artist's keen observation of nature and impassioned response to a world that included Hitler's death camps and Hiroshima.

Throughout his life, and irrespective of prevailing taste, Lebrun believed in art that was "engaged," as having a responsibility to deal with the existential theme of the human predicament, to address, and even redress, the evils of the modern world. Reflecting the mid-century angst provoked by war and the ever-present threat of nuclear annihilation, he remarked: "What I have to say, I say with Sartre, Kafka, Camus...in the midst of disaster, act as if you could mend that disaster every day." A profoundly humanist painter, Lebrun was devoted to the figure, believing it to be the vehicle through which subjects of universal significance could best be addressed. In 1960, however, Lebrun's adherence to figurative tradition was at odds with the "advanced" art of the day and particularly Abstract Expressionism, the style that dominated postwar painting in this country. Although Lebrun shared with the Abstract Expressionists a predilection for grand scale and the "heroic," painterly gesture, he resolutely stopped short of non-objectivity and rejected the introspection and intensely personal, self-expressive nature of their work. In the words of art historian Peter Selz, "by and large, he stands as a controversial and solitary figure, and the Genesis mural, a religious painting created during a non-religious age, remains a unique act."